ECB AND FED POLICY OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORKS – A PRIMER

CORRIDORS AND FLOORS - SOFT AND HARD

In the money and finance sectors, little is currently happening in the Euro Area. The ECB Watch Tool mainly derives from the OIS curve, indicating that market expectations are for the ECB´s policy rate to remain steady at 2% until September next year, which pleases the ECB “in a good place”. The German, French, and Italian stock exchanges have risen since 2023 at a similar pace to the US S&P 5000, as they include global firms whose earnings are not solely reliant on domestic economies.

Things are busier in the US, but it is anyone’s guess whether the FED will cut in December, despite markets already assuming that and applying pressure on the FOMC. The liquidity stress in the US money market, which I mentioned in my two previous posts (here and here), appears to have been resolved after a meeting on the 13th at the FED with primary dealers to discuss the situation and the operation of the Standing Repo Facility. The concern was that, out of fear of stigma, they were not using the SRF enough, which meant it was not functioning as intended to contain the increasing Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). Since then, things have stabilised. The SOFR rose once more this week, but the SRF was used immediately, amounting to $24 billion, which affected the rate. This movement is typically linked to the end of the month when higher liquidity use tends to create some pressure, particularly at the end of each quarter. The future will reveal whether liquidity stress returns. Other concerns now occupy markets, from the uncertain future earnings of many AI firms enjoying high valuations to the struggles of average American consumers, who are hindered by slow hiring, fears of layoffs, and high prices.

So, due the relative popularity of my two previous posts (here and here) on issues with the US money market and FED policy, as well as the publication of a speech by Isabel Schnabel, a member of the ECB’s Executive Board, which featured an excellent description of the new ECB framework for implementing monetary policy, persuaded me of the value of writing a post comparing the ECB and FED frameworks. With different motives—one by choice, the other by practical adjustment—both cases have evolved into what can be called a “range floor system,” where the overnight unsecured market rate is maintained within a range of 15 and 10 basis points, respectively. It is a floor, but some refer to it as a “soft floor” because it is not a single fixed rate, unlike the unique reserve remuneration rate in a full-fledged floor system.

1. INTRODUCTION

As it is well known, the ECB and the FED define the target of their conventional monetary policy of changes in their interest rates, as being the overnight unsecured rate formed in the money market where their liabilities (deposits or bank reserves) are transacted, the €STR (Euro short-term rate) for the ECB and the FFR (FED funds rate) for the FED. However, in addition to unsecured rates, there are also secured rates resulting from the use of overnight repurchase agreements (repos) collateralised by securities. Both rates represent the price of money for 24 hours. This question is less relevant in the Euro Area (EA) than in the US because repos are done using sovereign bonds, and there are 20 countries, of which only 12 have significant repo markets, with different ratings and, consequently, diverse repo rates. On the other hand, repo rates from the larger countries have been close to the €STR and below it, as is normal for secured rates. In the US, the situation is entirely different: there is a single overnight repo rate (SOFR), which is usually above the unsecured Fed funds rate. This last aspect is explained by, among other things, 1) the fact that the unsecured market volumes are now tiny and overwhelmed by the offer of cheap funds by the GSEs (Government Sponsored Enterprises), in particular the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB); 2) the overnight repo rate is pushed upwards by dealers huge demand to fund with repos their inventories of Treasuries. So, the difference is not so much about credit risk as about the composition of institutions’ participation in the relevant markets.

On the other hand, it’s worth remembering that the secured rate has far more weight than the unsecured rate. Particularly after the 2008 crisis, the volume of unsecured transactions fell dramatically. The US overnight repo market provides around $3.200 billion in financing, whereas the unsecured market size hovers around $160 billion. (Source: the FRED Database) The SOFR is therefore quite relevant, and that is why the FED has to be concerned with its developments and spread with the FFR, which, since 2021, the Standing Repo Facility has been used to control. Another reason for the FED to worry about the SOFR results from its role, when very high, is that it could possibly unravel the basis-trade done by hedge funds (almost $2 trillion), which disturbs the market for Treasuries as it did in 2020 (see my explanation here).

2. FROM SHORT TO LONG-TERM RATES

The transmission of short-term money market rates to longer maturities is essential because it is well established that medium-term market rates, particularly the 10-year yields, are what influence expenditure decisions on consumer durables, housing, and business investment, as well as valuations of equities and real estate.

So, decisions on very short-term interest rates are made based on the assumption that these rates significantly influence medium- to long-term rates, which in turn affect expenditure choices and asset valuations. Both channels have doubts, limitations, and caveats. Regarding the transmission of long rates to expenditure, there is a consensus around three points: first, that their effectiveness is asymmetric, being higher during economic booms or periods of high total debt than in recessions or low debt situations; second, that their efficiency has declined since the 1980s; third, that many other factors influence these variables, but the impact of long rates is mainly seen in housing, consumer durables, and asset valuations, and is relatively weak for business investment.

Regarding the transmission from short-term policy rates to 10-year yields, the impact has been quite weak since the late 1990s and 2000s. Naturally, medium- and long-term rates are market-driven and influenced by many factors, such as foreign capital flows, fiscal outlook, investor expectations on future growth and inflation, and the need for risk and a term premium. During the 2007-8 crisis, central banks resorted to unconventional measures to influence long-term rates, such as “forward guidance on rates” and large-scale securities purchases (QE). The intense media and market focus on every decision and statement by central bankers is largely due to the immediate short-term effects of their actions on market valuations (equities) and, temporarily, on long-maturity bonds. Sometimes, even in the short term, other factors mentioned can push yields in the opposite direction of the central bank’s policies. Examples include the “Greenspan conundrum,” when the FED raised the FED funds rate by 150 basis points in 2004 without affecting 10-year yields, or when, in September 2024, the FED cut rates and 10-year yields began to rise—an effect also observed after the recent cut on 29th October. The effectiveness of traditional monetary policy, which uses changes in very short-term rates to influence long-term rates, remains challenging and sometimes weak. Naturally, in episodes of sustained and significant increases in short-term rates aimed at fighting inflation, the impact on longer-term rates is felt, though not always proportionally.

3. THE OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORK TO ACHIEVE THE SHORT-TERM MONEY MARKET TARGET RATES.

3.1 THE ECB CASE

1. From the corridor system to the floor system

To manage the overnight money market rate, the ECB initially adopted a “corridor system” and an auction-based system to supply liquidity to banks in a controlled manner. The Main Refinancing Operation (MRO) rate was set through auctions (subject to a fixed minimum). Surrounding the MRO rate, there were two permanent facilities with fixed rates above and below it: the Marginal Lending Facility (MLF), which provided liquidity outside auctions at a penalty rate, and the Deposit Facility Rate (DFR), which allowed banks to deposit excess liquidity at a lower rate. The main refinancing operations (MRO) were weekly, but there were also 3-month small operations (LTRO) and occasional fine-tuning operations (FTO) of specific maturity. All operations required collateralisation by securities. During the financial crisis, the ECB issued LTROs lasting up to 3 years and Targeted LTROs (TLTRO) for durations up to 4 years.

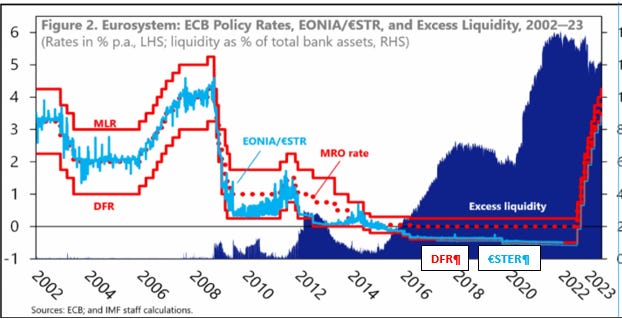

The challenge of operating a “corridor system” to closely match the targeted overnight market rate was due to the need to reliably estimate weekly demand for reserves (primary liquidity CB’s deposits) to adjust the level of supply that would set the market rate at or near the target. In the early years, the ECB leaned towards tight liquidity, and market rate volatility emerged around the MRO rate as a consequence of the auctions. In the chart below, the MRO rate is shown by a dotted red line and the overnight market rate is in blue.

When the 2007-2008 crisis started and the money market froze, the ECB cut rates and introduced a Fixed Rate Full Allotment system for its MROs to supply all liquidity/reserves demanded by banks. For precautionary reasons, banks required reserves well above the mandatory minimum, and the excess reserves (shown in dark blue) pushed the market rate (then EONIA) close to the Deposit Facility Rate (DFR). They nearly matched when the ECB began QE in early 2015, and the volume of excess reserves rose sharply. In practice, the ECB created a “floor system,” which occurs when abundant bank reserves make the market rate nearly equal to the rate the central bank pays on excess reserves. This same floor system started in 2008 in the US, when the FED was authorised to pay interest on bank reserves.

The convergence of the two rates occurs for two reasons: a) borrowing banks in the interbank market can shop around among the many banks with excess reserves, ensuring they do not have to pay much more than the DFR to obtain funds in the market; b) banks with excess reserves will never lend them to other banks at rates below the DFR. The floor system has three significant advantages.

1) It provides a more reliable and simpler way to steer the overnight money market rate, which is the aim of interest rate policy.

2) It introduces a new instrument to the monetary policy toolkit: the CB balance sheet size, which can be used during episodes of liquidity stress without impacting the target interest rate. In the corridor system, this is not possible.

3) Because the floor system implies a somewhat larger balance sheet than in previous frameworks, it is beneficial for financial stability, as the increase in bank reserves expands the supply of safe assets that have been scarce since the big financial crisis.

2. The new operational framework

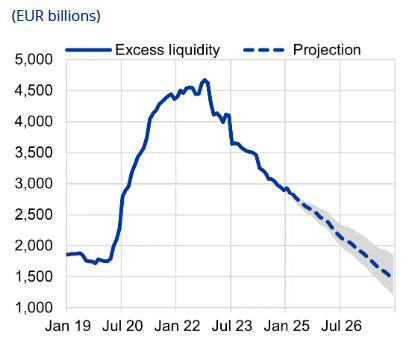

In March 2023, the ECB started reducing its balance sheet by not reinvesting the securities purchased under various QE programmes. The following chart shows the reduction of excess bank reserves that has been implemented and is forecasted to continue until the end of next year.

The Quantitative Tightening (QT) programme indicates a sustained reduction in excess reserves and, consequently, will bring an end to the floor system once reserves diminish. This necessitated the ECB to define the operational framework for when that transition would occur in the coming years. The decision was made in March 2024, and the new regime started implementation in September of that year. The new framework is a hybrid, comprising: 1) a primary component of demand-driven reserves through Main Refinancing Operations (MRO) supplied at a fixed-rate full allotment (FRFA); 2) the utilisation of 3-month LTROS at FRFA, and later structural refinancing LTROs with longer maturities; 3) a structural portfolio arising from securities purchases, which, alongside the structural LTROs, will maintain a regime of relatively ample reserves; 4) the fixed rate at which the MROs will be conducted is adjusted to keep a spread of just 15 basis points with the Deposit Facility Rate (DFR), which was previously 50 basis points.

The overriding operational principle of the new framework is, in the words of the ECB, “The Governing Council will continue to steer the monetary policy stance through the DFR. Short-term money market interest rates are expected to evolve in the vicinity of the DFR with tolerance for some volatility as long as it does not blur the signal about the intended monetary policy stance.”

To keep the DFR as the policy rate, there must a certain degree of excess reserves, meaning a surplus of reserves above those strictly demanded by the banks in the short-term (e.g. weekly). Only with a degree of excess reserves would the mechanism I mentioned above ensure the overnight market rate converges to the DFR. That is why the ECB decision also states that: “ New structural longer-term refinancing operations and a structural portfolio of securities will be introduced at a later stage, once the Eurosystem balance sheet begins to grow durably again, taking into account legacy bond holdings. These operations will make a substantial contribution to covering the banking sector’s structural liquidity needs arising from autonomous factors and minimum reserve requirements (VC underlying). The structural refinancing operations and the structural portfolio of securities will be calibrated in accordance with the above principles”

This understanding implies that the accumulation of structural reserves must occur before the current holdings of securities resulting from past QE are fully cleared. A significant layer of structural reserves needs to be established. Otherwise, if reserves are provided solely through MRO operations, the overnight market rate would tend to align with the MRO rate rather than the DFR (the deposit facility rate), which is contrary to the ECB´s Governing Council’s stated objective.

In my interpretation of the Governing Council decision text, the structural LTROs and the structural portfolio built up by purchasing securities will have to keep a layer of excess reserves sizable enough to ensure the exact implementation of what I called the overriding principle of the new framework: that the DFR is the ECB´s policy rate. or, as the document says that “Short-term money market interest rates are expected to evolve in the vicinity of the DFR with tolerance for some volatility as long as it does not blur the signal about the intended monetary policy stance.” To dispel any ghosts, it´s worth noting that correctly implementing the new regime has nothing to do with QE and its massive amounts, which were intended to support monetary policy objectives regarding medium- to long-term rates.

In this context, the definition of a 15 basis points spread between the DFR and the MRO rate can only be seen as a tool to limit any volatility above the DFR if, by accident or incorrect forecasting, the level of excess reserves becomes inadequate in particular market circumstances. Normally, this volatility should not be fully utilised.

The new system does not represent an attempt to go back to something close to the old corridor system, with the objective of keeping scarce reserves and a small balance sheet. The new market realities were, fortunately, well understood.

3.2. The FED case

As we will see now, the FED also has a “range floor” in its framework, but it results not from a specific choice, rather from a necessity caused by the fact that some relevant non-bank institutions have access to the interbank overnight money market (FFR), but cannot benefit from the FED remuneration of bank reserves, the IORB rate.

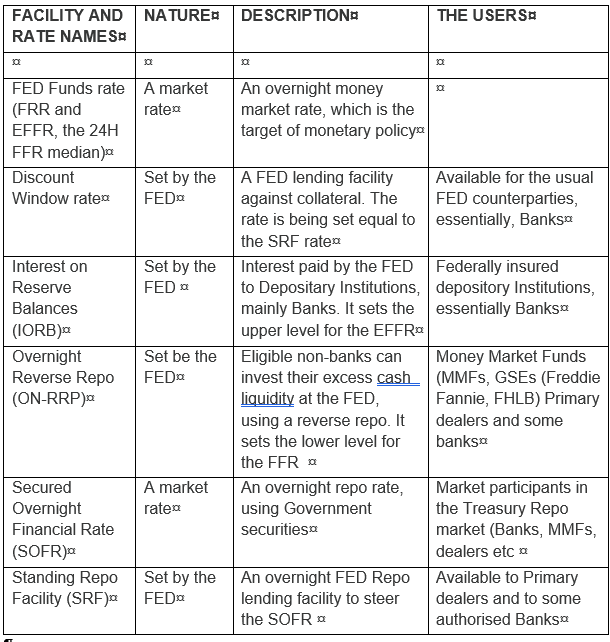

The entire operational framework is much more complex in the US case because the FED had to introduce several additional facilities to maintain some control over the overnight repo rate and to ensure an ultimate floor for the Federal Funds Rate (FFR).

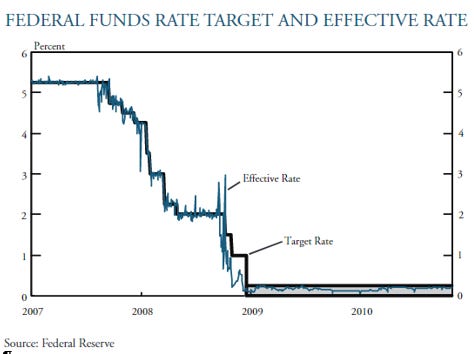

Before the 2008 crisis, the FED did not operate a pure corridor system because it could remunerate the banks’ reserves and therefore did not have a permanent facility at a rate below the FFR. There was a Discount Window Rate, higher than the FFR, at which banks could obtain liquidity against collateral. However, this lending facility was rarely used, as it often carried a stigma; banks using it were seen as too weak to obtain liquidity in the money market, which damaged their reputation and creditworthiness. Monetary policy was conducted through open market operations, involving the purchase or sale of Treasury securities, to adjust the liquidity in the market so that, given the estimated reserve demand by banks, the interbank overnight rate (FFR), the target of monetary policy, would remain close to the FED’s target. Due to difficulties in estimating this demand, there was always some volatility in the FFR around the declared target.

All that changed in the autumn of 2008 when, in November, the FED started the first large purchase program of Treasuries, inaugurating Quantitative Easing (QE). The purchases implied crediting the Banks’ accounts at the FED with the large amounts involved. Suddenly, there was ample liquidity and bank reserves. Without remunerating reserves to establish a floor for the FFR, it could go to inconveniently low levels. Fortunately, a law was passed in 2006 authorising the FED to pay interest on reserves, but it did not take effect until five years later. Those five years vacatio legis had to be reduced, and that was concluded at the beginning of October, allowing the FED to begin QE on November 25th. The following chart illustrates the effect of the market FFR immediately collapsing to the rate of interest paid to bank reserves at the FED. The “floor system” had been established with all its features and advantages.

The FFR was not precisely the same as the new IOR rate (Interest on Reserves), and therefore, the FED began in 2008 to announce a narrow range for the FFR target, given the difficulty of defining a single figure. Initially, there were two remuneration rates: one for normal reserves and the other, the IOR, for excess reserves, but these were unified in 2021 into the current IORB (Interest on Reserve Balances).

In January 2019, the FED´s FOMC confirmed that it was adopting for the future a floor system of “ample reserves” by communicating that “ The Committee intends to continue to implement monetary policy in a regime in which an ample supply of reserves ensures that control over the level of the federal funds rate and other short-term interest rates is exercised primarily through the setting of the Federal Reserve’s administered rates, and in which active management of the supply of reserves is not required”.

The story of monetary policy targeting the FFR did not end in 2008. The market FFR started to fall below the IOR because some institutions were authorised to apply their excess liquidity to the interbank money market, where deposits at the FED are transacted, and the FFR is determined. Besides the branches of foreign banks and some international institutions, the other significant institutions that have access to deposits at the FED are the so-called GSEs (Government-Sponsored Enterprises) active in the housing loan market: Freddie Mac and the FHLB (Federal Home Loan Banks). These institutions, however, cannot receive any FED remuneration on their reserves (deposits), so they offer them in the Federal Funds market. Since 2008, banks have almost ceased conducting unsecured transactions, so the FFR is dominated by liquidity provision by non-banks. Notably, the FHLB holds ample excess liquidity, which adds to others’ liquidity and pushes the FFR below the IORB (formerly IOR). In 2013, the FED introduced an experimental reverse repo programme to establish a real floor for the FFR. By using its securities holdings to do repurchase agreements to extract cash from the market at a rate set by the FED, it has created this new floor. Reverse repos are known as RRP agreements, in which the RP stands for Repurchase. In 2015, the new facility became permanent and is called the Overnight Reverse Repo Facility (ON RRP). Banks, GSEs, Primary Dealers and Money Market Funds have access to the ON RRP. The usual spread between the IORB and the Reverse Repo Facility has been 10 basis points, defining a narrow range within which the FFR has hovered. Consequently, there are two floors: the IORB rate for banks and the ON RRP for non-banks permitted to hold deposits at the FED.

To complete the full picture of liquidity facilities and administered rates overseen by the FED, the missing component is the overnight repo market. As the repo market expanded significantly and became dominant, high repo rates can trigger the unwinding of basis trades executed by hedge funds (see my explanation here). In response, the FED introduced a Standing Repo Facility (SRF) in 2021 to better control the repo rate and avoid the sudden and large interventions it had to carry out in the past (2019, 2020).

The following table concludes the post and summarises all the facilities and rates involved in the FED’s implementation of monetary policy.

Thank you for this excellent - well organised and presented- masterclass in contemporary monetary policy.

It seems that IOR only introduce opertionl difficulties. Could you explain what the in-pinciple advantage of IOR IS? [after 2008 is seems only to have reduced to effectiveness of QE.]]