A FEW CONCERNS ABOUT THE ECB'S NEW MONETARY FRAMEWORK

Lessons from the recent inflation, the role of uncertainty, gradualism and supply shocks

The ECB announced at its Forum on Central Banking in Sintra its new strategic framework, outlining the general principles for conducting monetary policy. It includes a single significant difference from the previous framework: a statement about the circumstances under which the ECB would use interest rates forcefully, presented in an unconditional sentence that does not mention the role of supply in causing inflation. I discuss three points: 1) the concerns that this may raise, 2) the wording in the text that might alleviate those concerns, and 3) the importance of learning the appropriate lessons from the recent inflation episode from 2021 to 2024.

1. Differences and risks of the new monetary policy strategic statement

There are a few significant differences compared to the monetary policy strategy approved in 2021. The policy target remains at 2% inflation in the medium term. The tone of the statement is more detached from the period of very low inflation that lasted for two decades before 2021. The increased uncertainty now and the higher likelihood of supply shocks will lead to the use of scenarios for communicating policy. The concept of employing scenarios instead of point forecasts or fan charts was recently suggested by Charles Goodhart (2023) and Ben Bernanke (2024).

The ECB will not eliminate the publication of forecasts and omits whether it will follow Goodhart's recommendation to disclose the policy reaction related to each described scenario, which would be the only way to make the publication of scenarios useful.

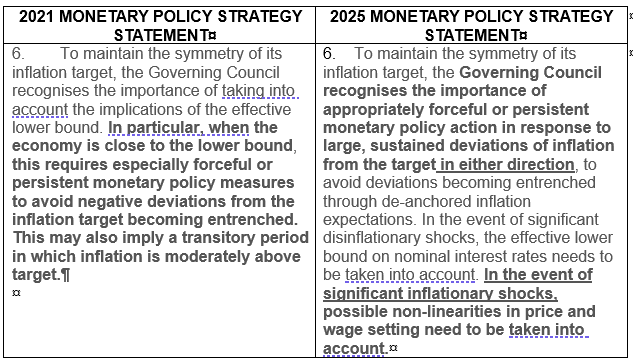

In the table below, you find side by side the texts that display the significant policy difference between the 2021 and 2025 statements.

As we observe, the new text appears more hawkish under a misleading sense of symmetry. The 2021 statement only mentioned “forceful or persistent” in cases of negative deviations from 2%, acknowledging the possibility that such policies could lead to “a transitory period in which inflation is moderately above 2%”. This valuable insight has now been removed.

Assuming that the “sustained deviations” from the 2% target are caused by supply shocks, as happened in 1973 and 2021-2023, it might seem at first glance reasonable to discuss deviations “in either direction”. However, this is superficial because, in reality, there is no symmetry in monetary history between inflationary and disinflationary supply shocks. The former are more common and particularly much more impactful. In comparison to large oil price increases that trigger an inflationary jump, we cannot even theoretically imagine, let alone empirically observe, a disinflationary shock with the same kind of sudden effect. Therefore, in practice, no symmetry exists.

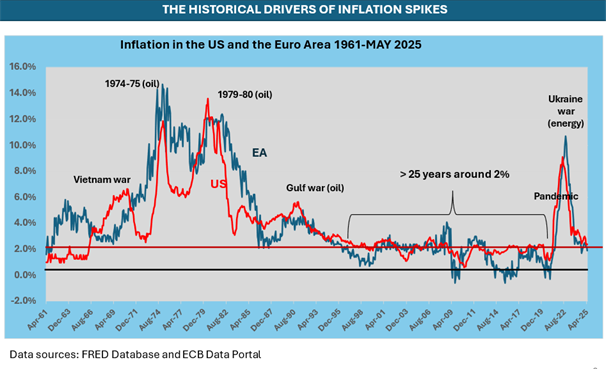

Examine the following slide, illustrating the evolution of inflation in the US and the Euro Area countries since 1960.

Figure 1

Inflation spikes in advanced economies were historically linked to wars, major commodity price shocks (energy, food), and a pandemic. These shocks were always temporary, although their durations varied, because such supply shocks cannot occur repeatedly in consecutive years. The 25 years of inflation remaining around or even below 2% in both regions were not caused by recurring negative supply shocks of lesser magnitude, but by restrictive macroeconomic policies, the decline of wage-price spirals, and low productivity growth during the period later described as suffering from “secular stagnation”.

All evidence suggests that supply shocks, particularly those of external origin, play a significant role in causing inflation episodes. This implies that Central Banks should avoid making unconditional statements about monetary policy without factoring in this element. The risks of the new ECB´s monetary policy strategic statement

The risk that a Central Bank fails to recognise the inevitable temporary nature of a supply shock inflation lies in potentially resorting to forceful or exaggerated increases in policy interest rates, thereby unnecessarily raising the costs of controlling inflation. I will demonstrate this below. The risk becomes even more significant because some ECB officials believe that Taylor's principle, which states that the interest rate should always be above inflation, applies to the 24-hour policy rate at all times, regardless of the presence of temporary supply shocks. Taylor's principle is a necessary mathematical condition for ensuring a uniquely determined solution in rational expectations models of the early DSGE type. Such simple, stylised models say little about reality. There are even academic papers, such as Angeletos and Lian (2022), showing that Taylor's principle is not strictly necessary in such models. Nonetheless, the risks are real that a literal interpretation of the new strategy statement at that point may lead to hawkish policy mistakes.

During “corridor contacts” at the recent ECB Forum in Sintra, officials attempted to reassure me by pointing to the adverb “appropriately' that precedes “forceful and persistent monetary policy,” as if it embodies all the wisdom we expect in each policy decision. To be fair, they could also refer to the following sentence further down in the statement: “The flexibility of the medium-term orientation takes into account that the appropriate monetary policy response to a deviation of inflation from the target is context-specific and depends on the origin, magnitude and persistence of the deviation.”

Hopefully, this sentence will help prevent exaggerated and rapid policy rate increases when the “origin” and “magnitude' of the deviation from the target are caused by supply or cost-push shocks. Similarly, the lessons drawn from recent inflation experience, which I now turn to, point to the same direction.

1. Lessons from recent inflation

Central banks were heavily criticised during 2021-2023 by economists and analysts referencing the previous major inflation episode in the 1970s and early 1980s, associated with two oil price shocks and labour market tensions. The accusations were twofold: 1) they were late in raising interest rates, and 2) they did not raise them high enough to increase unemployment, “break the labour market and control inflation”.

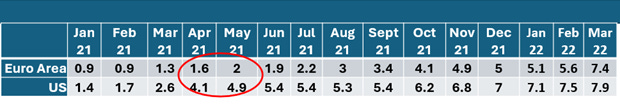

The first accusation has some merit, though less than usually considered. The table below shows monthly inflation figures since the start of 2021. Headline inflation rose to 4.1% in April 2021 in the US, whereas it was still 1.6% in the Euro Area.

Figure 2

Inflation rose earlier in the US due to a larger fiscal response to the pandemic than in Europe. Oil prices in 2020 were on average 35% lower than in 2019 and began to recover during the second half of 2021 (see Figure 5 below). That recovery, combined with disruptions to global supply chains, appeared to justify the upward trend of inflation in Europe. As the pandemic had a stagflationary effect on the economy and a recession was emerging, Central Banks hesitated and adopted the view that the impact of external price shocks could be temporary, which they ultimately proved to be, albeit with a longer delay. No one could have predicted that the Russian invasion of Ukraine would occur in February 2022, with devastating consequences for energy and food prices. The FED began increasing rates in March, and the ECB only in July 2022. They should have started raising rates months earlier in a cautious manner, as the initial stages of inflation were unavoidable. In such circumstances, monetary policy's primary goal is to start raising rates to prevent second-round effects on prices and wages, as well as to keep medium-term inflation expectations stable by reassuring economic agents of their commitment to controlling inflation within an appropriate timeframe.

The delayed response and the use of the word "transitory," while inflation continued to rise, allowed the media and some economists to mock the CBs' "mistake," giving unwarranted credibility to the need for a much hawkish policy stance. Focusing on the Phillips Curve model of inflation, and drawing from the experience of the 1970s and 1980s, L. Summers, for example, assumed a single figure of 5% NAIRU and a historical sacrifice ratio of 2 (the percentage of unemployment or growth reduction necessary to lower inflation by 1%), and stated in June 2022: “We need five years of unemployment above 5 percent to contain inflation—in other words, we need two years of 7.5 percent unemployment or five years of 6 per cent unemployment." Others, like Jason Furman, considering the flat Phillips Curve, assumed an even higher sacrifice ratio and advocated for larger rate hikes “to break the labour market." They thought that inflation would not come under control without a recession. This is what had occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Volcker, as FED Chair, implemented that policy with high interest rates, reaching up to 20%, causing the worst recession since the 1930s depression. This was harshly criticised at the time by Nobel laureate James Tobin, who wrote in 1982: "Stop Volcker from killing the economy” by “high-interest rates, above the inflation rate by unprecedented margins." [1]

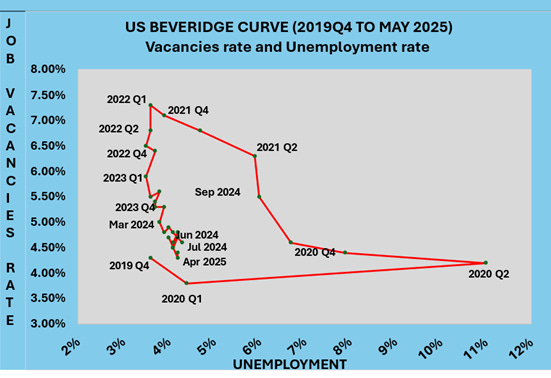

Similarly, there was a relevant debate concerning the evolution of the Beveridge Curve after the pandemic, showing a significant increase in the Job Vacancies rate, jobs offered and not taken (The Great Resignation), indicating pressure on wages that would worsen inflation.

Figure 3

The Fed's view on this development was that a simple slowdown in the economy would lower the Job Vacancy Rate without causing a significant rise in unemployment, enabling a soft landing. Blanchard, Domash, and Summers wrote in July 2022 a paper stating that this view was unrealistic, as it had never occurred before ─ a hard landing was necessary. The Fed responded in a Fed note, and a debate followed. Looking at the sharp downward movement of the Job Vacancies Rate without an increase in unemployment in Figure 3, it is clear that the Fed was correct.

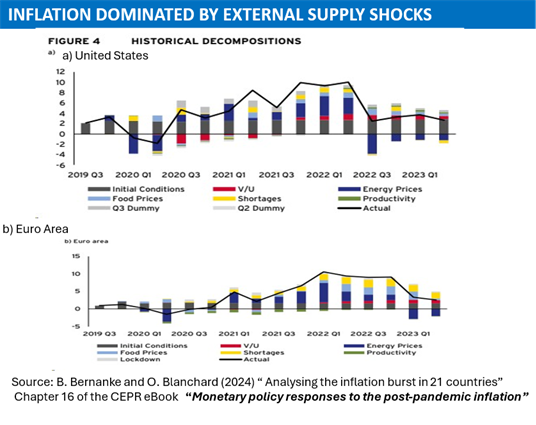

Later, in June 2023, Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard published a paper on the causes of pandemic-era inflation using a model that allows for the historical decomposition of the contribution of different variables over time to the evolution of inflation. In both the US and the EA, the labour market (red bars) makes a small contribution, whereas energy, food, and supply chain-induced shortages account for much more of the inflation's development.

This result arises from low coefficients of wage response to inflation (low catch-up) and low coefficients of short-term and long-term inflation expectations' reactions to ongoing inflation.

Figure 4

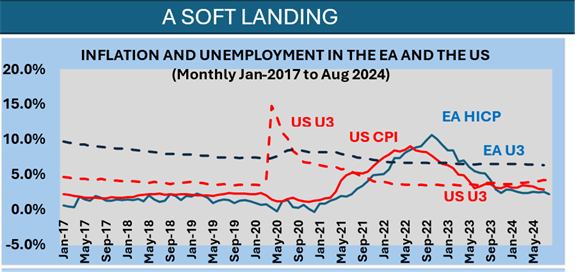

The model's overall results, based on its coefficient estimates, were replicated in 2024 across 10 additional countries. Understanding these findings is essential for answering the key question: what lessons can be derived from the inflation episode, particularly why inflation declined without causing a recession or increasing unemployment? (see Figure 5)

Figure 5

I believe there are three main reasons that explain that result:

1) International prices came down, the way it happened in all similar episodes

2) There was no price-wage spiral and only a moderate increase in unit profit margins

3) The Central Banks, contrary to the 1970/80s case, didn´t increase policy rates above inflation.

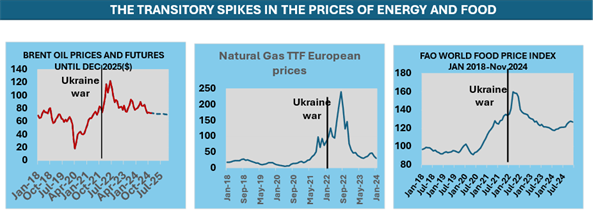

1) The first point is well illustrated by the following charts. During the 2021-2024 inflation episode, the pandemic, with its supply-chain disruptions and the Ukraine war, contributed to the temporary nature of energy and food price surges.

Figure 6

2) Regarding the second point, the absence of price-wage spirals can be attributed to the sharp decline in the number of workers belonging to trade unions and the diminishing role of collective bargaining in wage setting. For the US, a recent NY FED Staff Report describes how these developments have led to wages being essentially “posted by firms”:

“…shocks pass through to wages only to the extent that higher cost of living improves workers’ outside options, such as competing jobs or unemployment, relative to their current job. However, higher cost of living lowers real wages at all jobs evenly, and unemployment is rarely a credible outside option. We conclude that wage posting and on-the-job search limit the scope for pass-through from prices to wages.“ …

“In many advanced economies Union membership has declined dramatically, and evidence suggests that in the US wage-posting is the most common, if not dominant, method of wage determination”

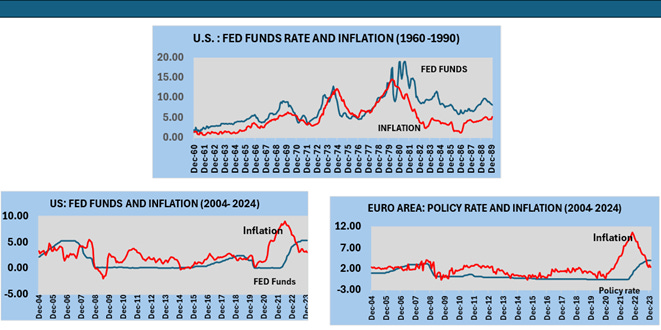

3) Finally, the last point is clearly demonstrated in the following slide, illustrating how Volcker in the late seventies pushed the Fed Funds overnight rate well above inflation, a behaviour that did not occur this time, either in the US or the EA, and inflation came down without a recession.

Figure 7

Conclusion

I hope that the lessons from the 2021-2024 inflation period have been properly internalised by Central Banks and economists, and that the Volcker mythology, applied in a different context and institutional setup, will not continue to cast its shadow over the present. In situations of significant supply shocks caused by external price spikes or supply chain disruptions, monetary policy should not preemptively decide on large hikes, but rather implement reasonable rate increases sufficient to anchor medium-term price expectations. Certainly, a literal interpretation of the new ECB Strategy Statement, which advocates for “a forceful and persistent” approach regardless of the origin and stage of inflation, would constitute a wrong policy. “Seeing-through” the initial inflation spike caused by a supply shock—when inflation is unavoidable—is the correct approach. In such circumstances, monetary policy should adopt a slightly longer horizon to achieve its targets, focusing on maintaining stable inflation expectations and limiting second-round effects (such as price-wage spirals). Furthermore, central banks should not always assume that inflation depends mainly on the labour market or that its degree of tightness can be measured solely by simple indicators of the domestic economy's slack, such as output or unemployment gaps.

[1] James Tobin (1092) at https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1982/08/15/stop-volcker-from-killing-the-economy/33a31ebc-a9be-4d8a-af21-cac6c32f2052/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

This is a very good read!

Fantastic review of the review. I agree with your conclusion.

Three observations:

1- it’s worth separating the US and European inflation stories because the drivers were so different. This ought to have different policy consequences.

2- I remain puzzled how little fine tuning the ECB seems to see needed in spite of the dramatic changes in the world. Granted, this may be the wise choice now, given the uncertainties.

3- I’m stunned that a policy review can include (as a pretty important place) a word like “appropriate”. What does this really mean? Has anyone ever seen policymakers suggest the need for “inappropriate” measures. You get my drift …